Do you remember when you first started writing songs?

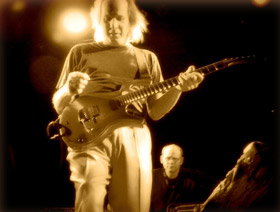

At age sixteen I contracted mononucleosis in high school and was forced to stay at home and be tutored for two months. And the requirement was that you be inactive. I was a drummer, and I could no longer drum. I had always had songs in my mind that would just appear, and I could kind of hear them full on as though a record was playing. So I decided to take those two months and teach myself to play guitar.

I borrowed an acoustic guitar from one of my band members, and by the end of the two months I had written five songs and put them on tape. I do remember little bits of pieces of them, but I couldn’t even tell you the melodies or titles.

The tapes are long gone?

I’m afraid so. I wish they weren’t. They’d be on my website right now.

Were you surprised at how quickly you picked up the guitar?

I was very surprised at my ability to just figure it out my own way. I could hear what I wanted and so I would just say, “Okay, this is the note that I want, and here is the harmony note to that. And if you put this other note with it you get an interesting chord sound that goes underneath it,” and just proceeded that way. I had absolutely no instruction from, really, anyone. And I didn’t try to learn it in a proper way. For many years I had no idea what the names of chords were.

So you just sort of intuited what the chords would be?

I think probably a lot of it was from my ability as a singer. Because from the age of five on I studied singing by just, you know, singing along with every record that I liked and every singer. I’d have to say that really my first musical ability was singing. I used to entertain my parents and aunts and uncles by singing along with the jukebox or singing with songs on the radio. And I just seemed to have a natural knack for harmonies.